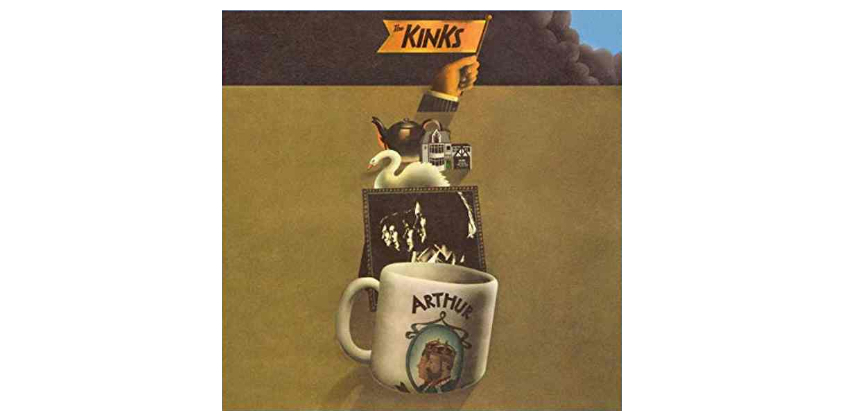

As is the case with many of the albums in the Kinks’ catalog, an argument could easily be made as to why Arthur (or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire) is a masterpiece.

Released in October 1969, preceded by Abbey Road and followed by Led Zeppelin II by a matter of two weeks, Arthur stands as a crown jewel in the songwriting abilities of Ray Davies and the musical arrangement abilities of The Kinks.

Originally intended as a televised rock play that was never produced, the album ended up evolving into a concept album of sorts which details the story of Arthur who emigrates to Australia due to the lack of work in a post-war England.

The album opens with Victoria which, despite being a hit in the UK and US, has never received the acclaim that it deserves. A driving rocker with exceptional guitar work, always stellar drumming, and an energy that hadn’t been heard on a Kinks album since their early riff based singles.

This track has all the makings of a Ray Davies classic. Descending bass lines, a virtual lack of form, lyrics that are at once poignant, humorous, scathing, and satirical, and a chorus that is insanely catchy. That they followed Victoria with the song Yes Sir, No Sir speaks volumes about their confidence as a band.

Yes Sir, No Sir is a haunting telling of military life from the point of view of a new recruit as well as from the point of view of the military itself. Again, seemingly without form, this song effortlessly flows through musical ideas, points of views, and styles all while being supported by one of the band’s best rhythm track performances. Mick Avory is the perfect blend of Ringo Starr’s inventiveness and Keith Moon’s manic style, and John Dalton may be rock’s most underrated bassists but this song is truly highlighted by Dave Davies and his exceptional lead guitar.

The album continues its dour turn with Some Mother’s Son which ranks high on the list of Ray’s most sad lyrics. “Some mother’s son ain’t coming home today” says all that needs to be said but in true Davies fashion, the idea is expounded on for three and a half minutes and the message just gets sadder and more heartbreaking.

“All dead soldiers look the same.” Wow.

It’s worth noting Avory’s drum work on this track. Although the tempo is rather slow and the arrangement is anchored over acoustic guitar and harpsichord, his performance is intense, driving, and loud. There are no rim clicks and soft hi-hats on this track, just full snare hits and ride cymbals.

Just when you can’t take another sad song, the band launches into a jaunty little bouncer about weekend driving. At the risk of sounding like a broken record, Avory’s drumming is, again, fantastic on this track and Dave’s lead guitar helps listeners stay attached to a chord progression that is virtually atonal. The verse is a series of fourths with the first chord descending in half steps along the way and the bridge shifts to minor without truly establishing a key only to cycle back to the chorus in a standard I-V back and forth in G. It’s clever, guys.

Brainwashed is next and it’s a fantastic rocker that doesn’t overstay its welcome. Stop me if you’ve heard this one before, Mick Avory’s drums. This tune is a great rocker that reminds us that The Kinks remain one of music’s best rock bands. It also serves as a quick palette cleanser before the side one closer, Australia hits listeners for nearly seven minutes.

Much like Drvin’, there is no confusing this track for anything other than perfect British pop. From the groove style to the melody to the background vocals, everything about this tune is deeply steeped in Englishness. Around 1:30 into the track, the band shifts into a half-time groove where the British quality of the melody is really highlighted. One wouldn’t assume that the song would eventually land on a jam lasting over three minutes but, shockingly, it does and the band sounds fantastic.

Side two opens with Shangri-La, a true Davies masterpiece, which would later be mimicked (copied, stolen…) by The Who for Behind Blue Eyes two years later. The song opens in a slow, simple fashion and after two verses shifts to major as the band begins to build. By the time the chorus hits, it’s chaos with a bass line that bounces all over the chords with a sixteenth note turn that makes the song rock. The arrangement continues to build and expand until all hell breaks loose for the new verse section at 3:00. Again, this song is nearly without form with so many new musical ideas flying in and out but unlike when The Beatles do it (Happiness is a Warm Gun, You Never Give Me Your Money), parts are reused and shuffled in and out and all seem to have been written at once as opposed to several songs spliced together. It’s nothing short of genius. Also, that bass line.

The album continues with Mr. Churchill Says which may be the first average song on the record. At nearly five minutes and with several verses of “talk-singing”, this track is saved by the band’s performance. At around the 1:40 mark, things kick into overdrive but, again, there is some talk-sing cheer leading as it drifts into another, less inspired, jam.

She’s Bought a Hat Like Princess Marina, however, counters the rock jam with a baroque pop ditty that opens with harpsichord and builds over every verse. The band clearly had a good time recording this track — you can hear them screaming with delight through all the fast parts. For the bridge, the tempo is pumped up a bit and some kazoos are added to the arrangement behind Dave’s country inspired solo. Then, Avory takes a drum break that launches the band into a vaudeville double time that totally cooks. It’s a highlight of the second side that seems to end 30 seconds too soon.

Things get soft as Ray’s sensitive side shines on Young and Innocent Days, a beautiful acoustic ballad that features some beautiful guitar work and a melody that even the best songwriters will wish they had written. Although it’s a slow song, the arrangement expertly keeps listeners interested with a quasi-classical approach taken to the overall feel. If there is a hidden gem to be found on Arthur (of the Decline and Fall of the British Empire) this is it.

Nothing To Say is the penultimate track and is a solid piano driven rocker. Like many of the tracks on this album, the bridge (also known as a middle eight) is more like a second verse and on this track that bridge actually saves the song from becoming a little too repetitive.

Then the album gets to the title track, Arthur. From the first measure of guitar intro, it’s clear that this song is going to be a good one and it doesn’t disappoint. The Kinks have an uncanny ability to record songs that feel like they’re in two different tempi and this tune fits into the mold pretty well. A driving rock beat with lots of drum fills and a lead guitar line with double picked passages somehow blend with a melody that feels like it’s being performed a few clicks slower. It adds excitement and the juxtaposition heightens both the band performance and the melody of the lyrics. It’s a fitting and appropriate ending to what has been an overall enjoyable listening experience.

This album came early in what would be an impressive string of Kinks masterpieces having followed Village Green Preservation Society and preceded Lola, Muwell Hillbillies, and Everybody’s in Show-Biz.

Despite its critical acclaim and its near perfection, the album wasn’t the commercial success that it deserved to be but, luckily, past commercial success has no bearing on current enjoyment and this album is a a wonderful listen from start to finish.

1969 was a big year for great albums but to rank Arthur anywhere lower than the top five is a wild misstatement that doesn’t take into consideration the impact and influence this album has had on artists in the 50+ years since its release. If time travel were possible, we’d all go back to a record shop in October 1969 and buy five copies each of this masterclass in songwriting, band performance, record sequencing, and lyric writing.